The Immortelle Lineage

Before Immortelle had a name, it had a temperament.

I grew up in the country, surrounded by open land, animals, and the quiet discipline of daily care. We had sheep. I had a horse named Hi-Rise, and through him I learned early what it meant to build a relationship through patience, repetition, and trust. Arabian horses, in particular, became a lifelong love — creatures defined not by ornament, but by structure, endurance, and presence. That understanding would return years later in unexpected ways.

Music came before fashion. I played the flute throughout school, practicing for hours each day with a singular goal: to earn first chair — and to keep it. It was the first time I understood dedication as a form of devotion. Mastery was not talent; it was repetition, discipline, and the willingness to work quietly while others stopped. That lesson never left me.

I was always creative, though I did not yet have language for what I was building toward. I won state-level awards for drawing while still in school, not because I chased recognition, but because making things precisely — until they felt right — was instinctive. I did not move easily between interests. When something claimed me, it claimed me fully.

Years later, when Immortelle began to take shape, it did so from these same foundations: structure, patience, endurance, and a belief that beauty is not accidental — it is practiced.

In 2013, long before there was a storefront, a festival booth, or a body of work to point to, I drew the Immortelle logo by hand and registered the domain. I did not yet know what Immortelle would become — only that the name carried weight, permanence, and intention. Immortelle is a flower that does not wither when dried. It keeps its form. It keeps its color. Even then, I was drawn to the idea of beauty that refuses to disappear.

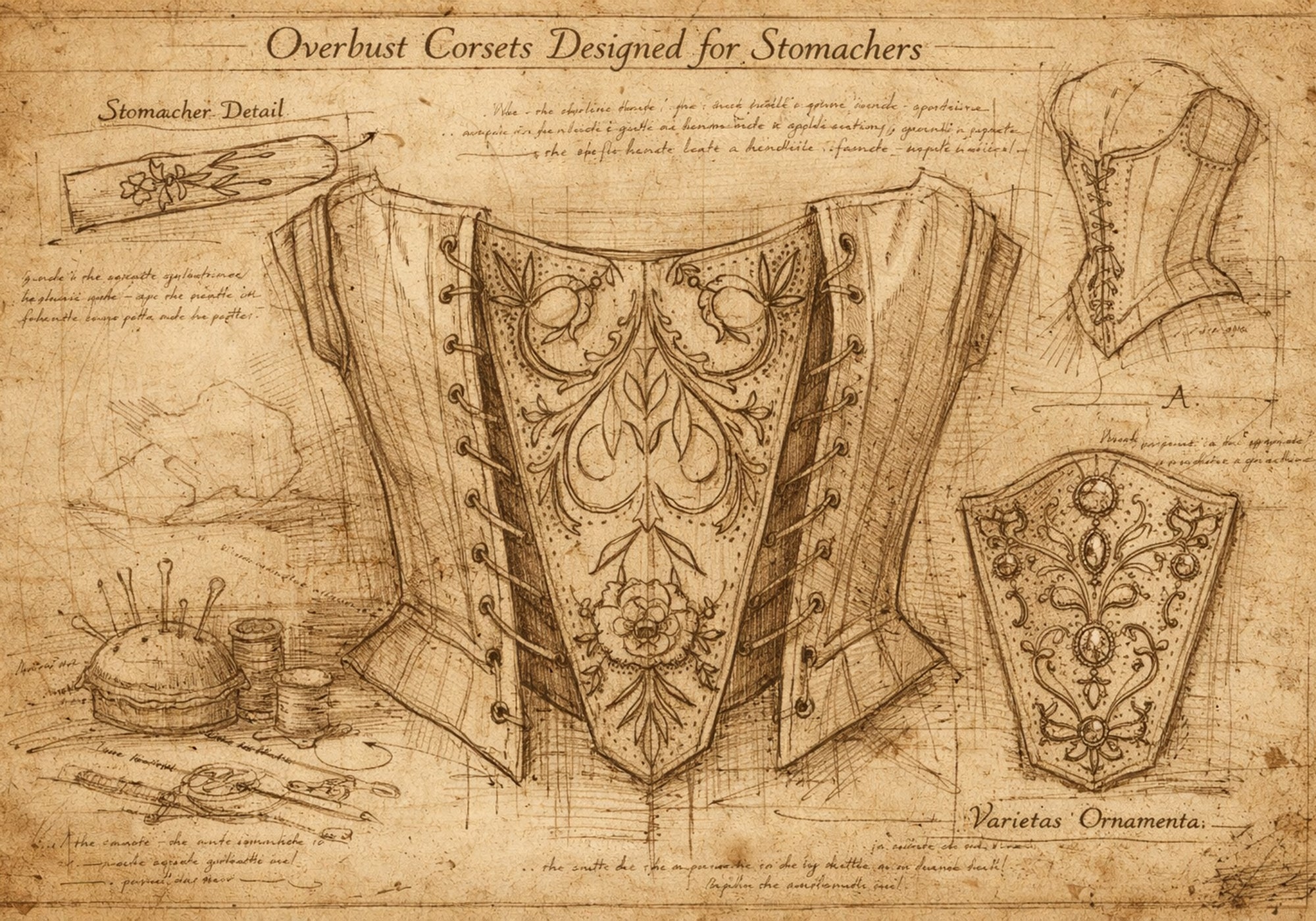

At its inception, Immortelle was meant to encompass my assemblage jewelry and the vintage jewelry components I curated — fragments with history, gathered and recomposed into something new. Jewelry felt like the most natural language at the time, but making things with my hands was not new to me. I have sewn for as long as I can remember. At eighteen, I was already constructing intricate dolls and fully realized garments for them — tiny sleeves, structured bodices, details no one asked for but I could not leave undone. Fabric, like metal, was simply another way to build meaning.

In 2015, I moved to Ohio and made the quiet decision to lean fully into my work. Jewelry making and the sourcing of vintage parts became not just passion, but focus. In the spring of 2016, I opened a small shop in Waynesville, Ohio, called Luminarium. It was a brief but formative chapter — a place where I made candles, sold my jewelry, and surrounded myself with beautiful oddities. Luminarium was not meant to last forever. It was a threshold space — a room where ideas could gather before deciding what they wanted to become.

Later that same year, I was offered two guest weekends at the Ohio Renaissance Festival.

I did not yet understand what that invitation meant.

Those two weekends would quietly alter the course of my life.

I accepted, unaware that I was stepping into the most fulfilling chapter I had ever known. For that first appearance in 2016, I purchased an open-air cart from an old carnival park — weathered, imperfect, and entirely humble. That cart became Immortelle’s first physical form. It held my jewelry, my hands, and my hope.

I was invited to stay for the remainder of the season, an invitation I accepted without hesitation. When the season closed, I was asked back as a guest vendor for the full 2017 run.

It was then that Luna entered the story.

Luna — a gypsy wagon I would later restore — became more than a booth. She became a presence. The year of Luna marked the true emergence of Immortelle. For the first time, I dressed my mannequins in garments I had hand-sewn specifically for them. These were not products yet — they were instinctive expressions, silhouettes I needed to see standing upright in the world.

The response was immediate and overwhelming.

Passersby stopped not just for the jewelry, but for the clothing. They asked if the outfits were for sale. They wanted to wear them. They wanted to become them. In those moments — surrounded by dust, music, and sunlight filtering through the acorn tree that shaded my space — I understood with sudden clarity: this was my calling.

Not just adornment, but dress.

Not costume, but presence.

That same year, I began searching for a sewing house to help bring my designs into the world for the 2018 season. I knew Immortelle needed to grow — not away from the handmade, but toward sustainability.

It was also during this time that the opportunity arose to purchase a permanent space at the faire.

The choice carried real weight. Until then, Immortelle had existed through motion — carts, temporary setups, seasons that packed themselves away at night. Buying a space meant choosing permanence over flexibility, responsibility over momentum.

It was the first time Immortelle made a commitment that could not be reversed.

Owning that space meant the work no longer disappeared at the end of the day. It remained visible. It accumulated continuity. It carried overhead, expectation, and consequence. The choice required faith not only in the work as it existed, but in the work it would need to become in order to sustain itself.

This was the true crossroads — the moment where Immortelle stopped being an experiment and became a house. Where making shifted into maintaining, and vision accepted the burden of permanence.

From that point forward, there was no returning to provisional ground.

The work had roots now.

It would either deepen — or fail.

Immortelle chose to deepen.

What began as assemblage became architecture.

What began as jewelry became silhouette.

What began as instinct became language.

Immortelle was no longer an idea I carried alone.

She was standing, dressed, and looking back at me.

This was the beginning of Immortelle Bijouterie — not as a brand, but as a life’s work taking its first true breath.

And everything that followed grew from that moment of recognition:

that making things was not something I did — it was who I was becoming.